“Violent psychopath” (21,700). “Psychopathic serial killer” (14,700). “Psychopathic murderer” (12,500). “Deranged psychopath” (1,050). We have all heard these phrases before, and the number of Google searches following them in parenthesis attests to their circulation in popular culture. We are fascinated by them, and yet each phrase embodies a widespread misconception regarding the psychopathic personality. But why are we so fascinated by them? What draws us to their study? In my opinion, it is the superficially charming nature and heightened intellect of psychopaths. It is also their ability to put emotions aside and act entirely without them. It’s undeniably fascinating, and equally as terrifying.

We associate the word, ‘psychopathy,’ with figures of extreme violence and manipulation, such as Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer and Charles Manson. However, we are also likely to encounter psychopaths working in normal functioning environments, including hospitals, where they are performing incredibly high pressure procedures without breaking a sweat. In Kevin Dutton’s fascinating book, The Wisdom of Psychopaths, he describes one of the greatest and most successful neurosurgeons as ‘ruthlessly cool,’ and ‘incredibly focused under pressure.’ The surgeon freely admits that he has no compassion for those he works on, because compassion is distracting in a room where every second counts. He talks about turning into a ‘cold, heartless machine, who is totally at one with the scalpel, drill and saw,’ because emotion has no place when he is cheating death. The words are disconcerting, but they make perfect sense. There are benefits to being a psychopath, which is quite difficult to comprehend. However, as Kevin Dutton eloquently states, the psychopathic arsonist who sets fire to your house is also more likely to be the hero who braves the flames to seek out your loved ones in a parallel universe. Psychopaths are very capable of putting emotions aside to do what is necessary.

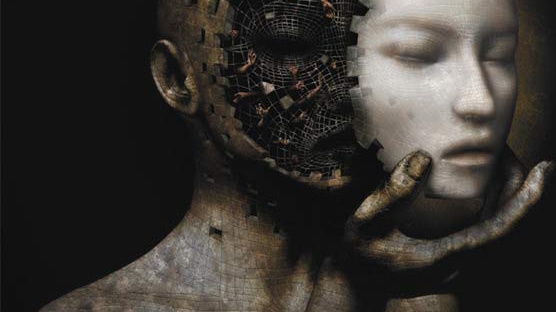

Claims like these are hard to believe, but they are true. Psychopaths are fearless, confident, ruthless and focused. These specific characteristics are certainly sought after for certain job positions, and recent studies have found that we are more likely to encounter psychopaths in the operating theatre, on the trading floor, and in a courtroom legal battle. Psychopathic talents can be advantageous, which is quite unsettling to consider. When harnessed to suitable situations, such as the hospital operating theatre, the psychopath becomes a truly valuable member of society. Unfortunately, our experiences of psychopathy are nearly always defined by what we have seen in popular culture. The term, ‘psychopath,’ is more likely to conjure images of Hannibal Lecter in our mind, rather than the somewhat terrifying but necessary brain surgeon who saves lives on a daily basis whilst detaching entirely from emotions and empathy.

Am I the only person in the world who wishes I could turn off my emotions at times? I certainly wouldn’t do it permanently, but the complexity concerning the psychopathetic condition is definitely thought-provoking.